One Rohingya woman’s story shows what’s at stake for so many refugees

At just 22 years old, Toyoba has already faced unimaginable hardships. A Rohingya woman from Myanmar and the mother of three daughters, she was forced to flee her village in October 2017 to escape a brutal campaign of persecution by government military forces. She and her husband, along with their daughters and other family members, escaped from their village at night and walked for 15 days through the mountains to reach safety across the border in Bangladesh.

Since August 2017, around 700,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar for Bangladesh. Like Toyoba and her family, they narrowly escaped with their lives and are now living in refugee camps, trying to regain some sense of normalcy despite the cramped, dirty living conditions.

The camps—like Kutupalong (below), which is the largest—are overcrowded. The smell of waste and small fires for cooking hangs in the air. Large families have no choice but to occupy small, one-room shelters fashioned from reeds and tarps perched in the mud.

A long journey, then an unwanted pregnancy

Not everyone in Toyoba’s family escaped safely to Bangladesh. Her 18-year-old brother was killed in the street by Myanmar’s military forces, and many other relatives are still missing. Those who did escape didn’t have time to gather their belongings.

“Even though we brought some food, we were starving for three days after the food ran out,” Toyoba says. Traveling on foot with her three young children was not easy, and everyone’s feet were swollen after the 15-day journey.

As the family tried to settle into their new life in the refugee camp, Toyoba began feeling sick, weak and unable to care for her children. She realized she was pregnant. Amid what she calls her “anxious life” as a refugee, she knew she didn’t want to have another child.

There are thousands of pregnant women and adolescent girls living in these camps—some victims of rape as they fled Myanmar—who feel similarly, yet they have little or no access to reproductive health care. Some resort to clandestine, unsafe methods to end a pregnancy, risking their health and lives.

Moving quickly to meet a critical health need

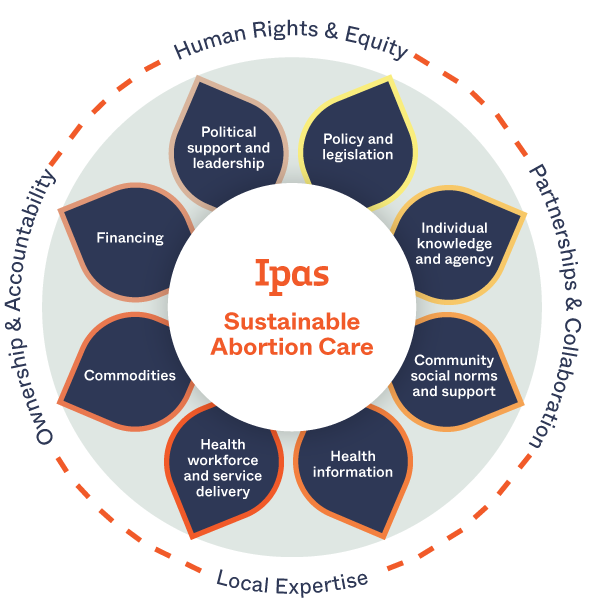

Recognizing that Rohingya refugees had an urgent need for reproductive health care, Ipas Bangladesh and partners began working quickly in late 2017 to improve refugees’ access to contraception and safe abortion care (called “menstrual regulation” in Bangladesh).

In just two months, services had been established at 10 facilities serving refugees. Paramedics, midwives and doctors who go through Ipas’s short training are providing menstrual regulation as well as treatment for complications of unsafe abortion.

Trainers and providers say they feel proud to be helping these refugees in need, and they’re encouraged to see that the word is spreading about the services they offer. “More women are finding out where to go and what to do, and that there are facilities to help them safely terminate a pregnancy,” says Dr. Zulekha Akhtar, an Ipas trainer. The task now is to keep expanding, so all the women and girls who want services have access to a trained provider.

A way forward

As her condition worsened and she worried about how to care for her family, Toyoba heard from a woman in the camp that she could safely terminate her pregnancy at a nearby health center. Her husband supported her decision, so she went and was able to receive menstrual regulation with pills from an Ipas-trained health worker.

“I am happy with the medicine I was given,” Toyoba says. She’s feeling better now—and more confident she can properly care for her children in this challenging new environment. She’d like to help other women in her situation access the reproductive health care they need.

“I will show them [where to go],” she says.

Ipas continues working with partners to ensure that women and girls in these refugee camps can prevent or safely end an unwanted pregnancy. We’ll keep training health providers who can help more refugee women like Toyoba regain some control over their bodies and lives.

Photographs and video © Farzana Hossen

For more information, contact [email protected].